1. I had a wonderful teacher

2. A family member introduced me

3. I played video games and wanted to make a gun that shoots hot dogs

In respect to games, and like many kids growing up in the 2000s, I played Halo CE semi-religiously. I remember preferring the campaign, but my older siblings were much more interested in taking advantage of my less-developed motor skills in local multiplayer.

Upon getting my first computer - a MacBook, ostensibly for schoolwork - I was fairly limited in the games I could play. But I could run Halo[2] - and, following on from the troubleshooting needed to get it up and running, I began to lurk online communities dedicated to modifying the game. I started with hexadecimal editing, then began poking around in decompiled game files with community-developed modding tools. Eventually, I came across a dialect of Lisp known as BlamScript[3] - and I started to learn my first programming language. The rest is history.

To this day, I’m impressed with how creative, erudite, and fundamentally sound the approach Bungie employed was in realising a memorable experience. The engine (so to speak) of this experience lies in their campaign AI.

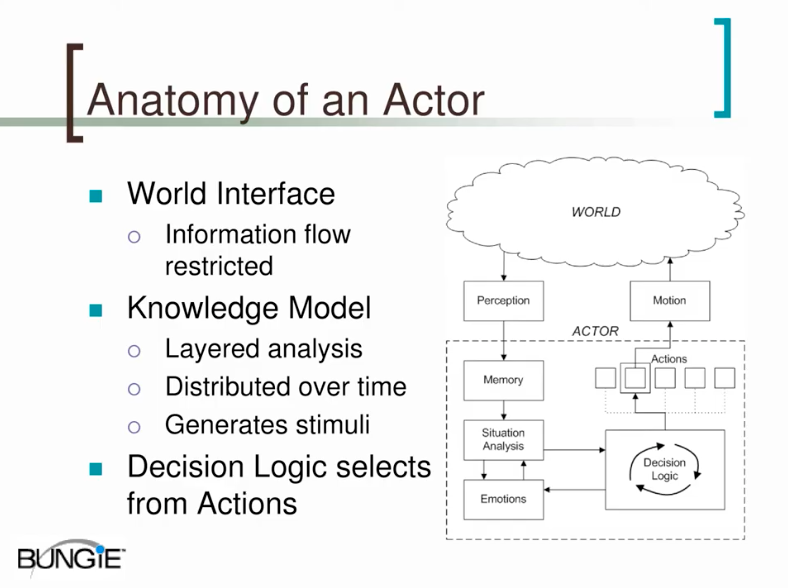

According to Bungie’s own designers[4], there were three key goals: enemies had to be unpredictable (to create novel experiences), intelligible (by broadcasting their intent to the player), and interactive (by acting believably and responsively to the player’s actions in the world space).

These goals were implemented in epicycles over the course of a mission via 'encounters', where the player (+AI allies) meets and fights group of enemies in the world and each encounter dynamically reacts to the player’s approach to these enemies. For example, the player might be directed to reach an objective with an interactive scripted object which advances the level state to the next objective. A group of enemies is spawned to defend it, and the encounter begins when the player reaches the point of engagement with this group.

This is the fundamental basis of the replayability they attained. The notion that they ‘defend’ this space is illusory; until disproven, the player assumes that the enemy knows the same things they do. But there is no higher-level ontological concept of ‘defend this object’ for squads of enemies: there are thresholds for group attack and retreat behaviours, physical bounds for the enemy actors to operate within, and individual actor responses dictated by their internal state.

The illusion of intelligence in this combination creates verisimilitude[5] for the player: a gamified, satisfying, and self-consistent experience of a world. This world is, of course, a far-future pulpy space opera where you play as a tank-green supersoldier brainwashed from childhood to be the perfect killing machine - but the point is a fun and (again) self-consistent world, not a real one.

Here are three actor voice clips from the game, each < 3s long, each corresponding to a specific behaviour by an individual actor (the ‘elite’ enemy):

Even without the filenames (e.g., "elite.pissed.01.mp3"), they parse pretty clearly. The first signifies some anger, then an engagement of the player; the second, extreme anger (accompanied in-game by an animation where the enemy shakes its head in rage, then charges the player); the third, mocking laughter after defeating the player (in the latter, they sometimes shoot your bloodied, supine corpse as well).

These represent aspects of the ‘racial personality’ of an elite actor. They’re confident, dangerous, and serve as leaders for the other types, or races, of the enemies. If this isn’t clear, here’s what a ‘grunt’ actor often says when you kill the elite leading the squad:

By hammering home the personalities of each enemy type with auditory feedback - and coupling them with animations - the player knows exactly what the enemy is thinking. Just as important, this unambiguous feedback means player can learn and develop a degree of skill in approaching them.

Supporting this was Bungie’s concept of an individual knowledge model. They wanted AI to know things about the world the same way that players did - i.e., through sight and sound. Enemies do not have omniscient knowledge of where the player is. They react to shots, explosions, comrade deaths, etc. They can also be fooled in a primitive capacity - shoot over in the corner while out of sight, they’ll examine where the projectile landed. Disappear behind cover, they’ll look for you where they saw you disappear - meaning you can circle around and sneak up behind them.

What’s really remarkable is that Bungie attained this using very limited hardware, particularly when considering the CPU budget.

The original Xbox relied on a 733MHz single core Intel Pentium processor, and only 15% of the total CPU budget was reserved for AI behaviour. They had to manage 20-25 actors, up to 5 vehicles, and the actors' responses to these alongside two players when in co-operative mode. The margins were fairly thin, even if the Xbox’s specs blew other comparable systems of the time out of the water.

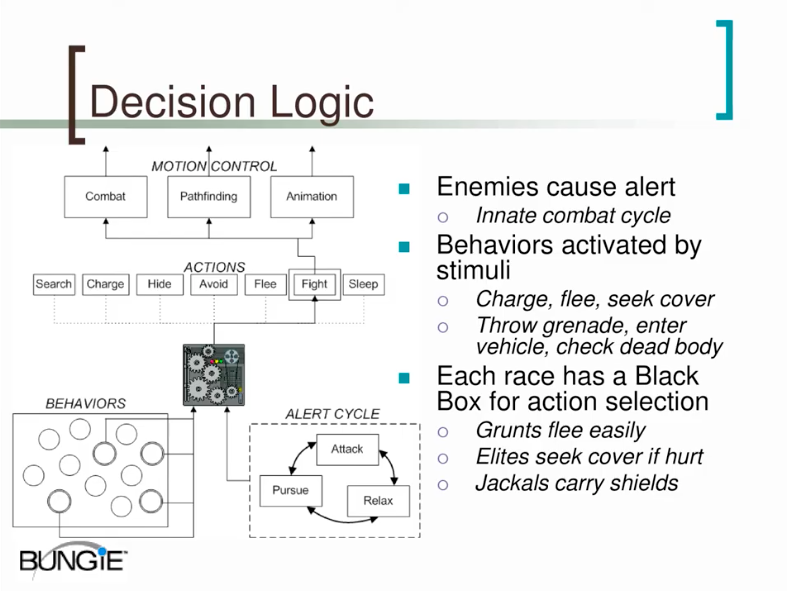

This limited budget meant Bungie had to make some creative decisions. One method was how they managed the actors’ internal states. By implementing analog (i.e., continuous signals as opposed to non-continuous digital) variables that the AI based their decisions around, they could keep encounters fresh, interactive, and undpredictable.

For example, they tracked two variables (among others) in this way: player distance and player health. Each actor type then had hard-coded behaviours they may, semi-randomly, choose to engage in based on these variables: elites might charge a low-health player in cover at close distance, or they might throw a grenade if high health and in cover at medium distance. On higher difficulties, one actor throwing a grenade might cause other actors to do the same - meaning a greater challenge as the player must leave cover to avoid death.

From the player’s perspective, this is smart behaviour. Approaching the same situation can be done countless times in different ways, which keeps the game fresh through unanticipated interactions with enemy actors.

Similarly important is how efficient and straightforward (for the time) it was to work with as a level designer. When actors have so much autonomy, redesigns and working with testing feedback becomes 10x easier (and Bungie loved to test).

These behaviours are so well-implemented and robust that, if you import a .actor file (and its needed dependencies) from the campaign and spawn it on a multiplayer map[6], it will function more or less exactly as it should in combat.

There are missing aspects like patrol routes, but these are hard-coded into the level design and can be replicated. A system like this distributes the work needed when telling a linear story, meaning that interactive and emergent behaviours can be staples of encounters in what is still a closed, carefully curated world.

I imagine that, to a game designer, I’m probably not saying anything totally unexpected. Many of these techniques are now foundational in FPS game design and elsewhere - if by different names.

For others, I hope I've illuminated what I see as an under-acknowledged step up in mainstream enemy AI design. Much has been made of the AI in the F.E.A.R. games for the same reason - and everyone knows how important Halo was on the whole. But I think certain aspects have remained underappreciated.

I’d liken it to watching Ridley Scott’s Alien or Aliens. At times, they appear a little predictable - but this is because they invented the tropes we're picking up on. You could say the same thing about Steven Spielberg’s films. Some things are popular because, perhaps emptily, they are calculated to follow on from what is popular: some things become popular because they are so good that they can’t be ignored.

Halo CE is a combination of these factors. It was created by a studio just hitting its true golden period (not to sniff at Myth or Marathon - they’re excellent games for their time) and had the advantage of Microsoft’s sponsorship as the flagship title for the original Xbox.

Perhaps more loftily, what I'm trying to communicate is something akin to what I felt when reading Douglas Hofstadter’s characterisation of the Lisp interpreter as a ‘genie’ in a 1983 Scientific American article[7]:

Let us now move on to the way Lisp really works. One of the most appealing features of Lisp is that it is interactive, as contrasted with most other higher-level languages, which are noninteractive. What this means is the following. When you want to program in Lisp, you sit down at a terminal connected to a computer and you type the word "lisp" (or words to that effect). The next thing you will see on your screen is a so-called "prompt" - a characteristic symbol such as an arrow or asterisk. I like to think of this prompt as a greeting spoken by a special "Lisp genie", bowing low and saying to you, "Your wish is my command - and now, what is your next wish?" The genie then waits for you to type something to it. This genie is usually referred to as the Lisp interpreter, and it will do anything you want but you have to take great care in expressing your desires precisely, otherwise you may reap some disastrous effects.

It was somewhat mystical, at the time, to have this experience - even if it has since become run-of-the-mill. This iceberg of development and change in software is reflected more visibly and understandably in games.

It's all "standing on the shoulders of giants" at higher levels of abstraction - but against an industry that's grown 100 times over since 2001 and the implicit knowledge, the implicit skill, of designers, these giants can become nearly invisible.

Much of the information in this article came from a lecture delivered by a couple of Bungie staff members at GDC 2002. If you’d like to know more, I’d encourage you to give it a watch for a deeper examination of the concepts I’ve referenced here.